The Cleveland clinic's most recent attempt to do a cadaveric uterine transplant did not meet with the desired endpoint. The uterus had to be removed because complications (Link). This was brought to my attention in a blog piece from the MD Whistleblower (Link). He raises some interesting questions but I think his questions should also touch upon implications in a much broader clinical and ethical realm. The circumstances of the transplant were the patient who received the transplant was born without a womb. As it turns out, there are many humans who are born without wombs, approximately half to be specific.

The Cleveland Clinic experiment seems like a bad idea at multiple levels. It is not as if no other options existed for this specific person. For the transplanted womb option to work, they had to go through the in vitro fertilization anyway meaning those eggs could have been implanted in a surrogate who did not need to take a host of immunosuppressive drugs for the entirety of the pregnancy. Frankly, I do not see how any IRB could approve this protocol. It places the person getting the uterus at great risk and places an unborn child at great risk, all of which is completely unnecessary for generating a child. Yes, it is a clinical trial but I simply cannot see how these types of risks can be justified. It appears to be reckless in my opinion.

The ability or inability to carry a child because of having or not having a uterus is one of basically an infinite set of human functional differences which exist because of inborn or acquired differences. The question I want to pose is what portion of these differences constitute fair game for correction via some sort of medical intervention? What sort of interventions should we strive to develop and which ones of these should be the target of investment of public dollars? As we move inexorably toward a world which defines access and payment for health care as a universal right, what of the inevitable desires of people to use the health care system to enhance functionality beyond what they were born with? Does that too represent an inherent human right?

Think of all the differences in inborn or acquired traits which could become fair game. I am not so tall and always thought it would be great to be taller, much taller. The fact that I am "vertically challenged" likely has had all sorts of impact on what success and failures I have encountered in life. Simple physical attractiveness (perhaps not so simple) has huge functional implications which has major impact on where people end up in the world. At his point height and physical attractiveness are already amenable to some form of rectification. Imagine all of the possibilities for enhancements that other interventions could impact.

Should this be within the realm of heath care delivery? We already have bleed through in terms of training and missions. Physicians trained in plastic surgery and increasingly other fields such as dermatology, are trained as physicians but have moved into realms very distinct from taking care of people with actual illness and sickness. Once we validate the mission to take people who are not sick by any typical definition of disease, and push the mission to create functionality that people were not born with, we are doing something very different. Before we open this Pandora's Box, we should be very intentional about understanding where it will take us.

Definitely not a follower: Following the herd will get you to where the herd is going

Sunday, March 20, 2016

Saturday, February 20, 2016

The worrisome role of hedgehogs in politics

I am a fan f the work of Philip Tetlock. He has studied the ability of individuals to forecast the future using a very clever approach, the details of which are beyond this specific blog piece. What Tetlock found in his initial work was that the best predictor that and expert was right or wrong was how recognized or famous they were. However, the correlation was negative. The more fame (or perhaps notoriety), the worse their judgement tended to be. Furthermore, the strongest correlation with correct predictions and judgement was related to cognitive styles which he referred to as either "hedgehogs" or "foxes".

Foxes use a cognitive style which is flexible, adaptive, and measured (tentative) while Hedgehogs are

Foxes use a cognitive style which is flexible, adaptive, and measured (tentative) while Hedgehogs are

said to "know one thing and know it well" and to focus on a single, coherent theoretical framework in their analyses and predictions. Quintessential Hedgehogs might be found on television or other media and promote themselves as experts. The most successful people in the realm are not tentative or reflective and they rely on the very brief attention span of the public to forget when they are wrong, and they are often wrong and may be worse than chimps guessing at random. However, they are decisive and attractive to the viewing public.

said to "know one thing and know it well" and to focus on a single, coherent theoretical framework in their analyses and predictions. Quintessential Hedgehogs might be found on television or other media and promote themselves as experts. The most successful people in the realm are not tentative or reflective and they rely on the very brief attention span of the public to forget when they are wrong, and they are often wrong and may be worse than chimps guessing at random. However, they are decisive and attractive to the viewing public.

This cognitive style has worked itself into a central place in politics. For some reason, we are now surprised when political candidates with notable hedgehog like tendencies are appealing to the public. Bernie Sanders is an off the chart Hedgehog. His big thing is income inequality and vilifying financial markets and institutions. Is there any nuance in his appeals? I have not seen any yet. For all of the criticism coming Hillary's way, one cannot accuse her of just knowing one thing well.

This cognitive style has worked itself into a central place in politics. For some reason, we are now surprised when political candidates with notable hedgehog like tendencies are appealing to the public. Bernie Sanders is an off the chart Hedgehog. His big thing is income inequality and vilifying financial markets and institutions. Is there any nuance in his appeals? I have not seen any yet. For all of the criticism coming Hillary's way, one cannot accuse her of just knowing one thing well.

expert class, holding expertise and information which are proprietary and he implies he will move America back to greatness through his own special will and special sauce. Both he and Ted Cruz push to motivate and unify people by vilifying and mockery, which is one of their big things.

expert class, holding expertise and information which are proprietary and he implies he will move America back to greatness through his own special will and special sauce. Both he and Ted Cruz push to motivate and unify people by vilifying and mockery, which is one of their big things.

As politics and the entertainment industries have become blurred in terms of where one ends and another begins, it is not surprising that characteristics which make individuals attractive as entertainers and maintain ratings turn out to be the same characteristics which make them attractive to the voters. This is not new. JFK perhaps ushered in this phase of politics. His family links to Hollywood were strong and his father Joe understood the importance of image and simple and compelling ideas, whether they were right or wrong. Ronald Reagan was the master of this domain and he was a hedgehog.

What is worrisome is these same hedgehog like characteristics are also basically markers of bad judgment. How do we address this? Is it addressable? I suspect it is not and represents a basic human limitation. One approach may be to push to limit the ability of parties to appeal to voters through some sort of legislative or regulatory action. I have little confidence that this will yield results which leave us better off. In my opinion, these observations represent a compelling reason to create limits on what should or can be done via exercise of political power.

The Republican may be similar. Donald Trump may be hard to characterize as a typical hedgehog, but I believe he is. His one big thing is his experience in business allows him to make deals and "Make America Great". It is a simple hedgehog like message. His reality show suggested that one can makes one's organization simply by firing people. He is an odd expert but he fits into the

As politics and the entertainment industries have become blurred in terms of where one ends and another begins, it is not surprising that characteristics which make individuals attractive as entertainers and maintain ratings turn out to be the same characteristics which make them attractive to the voters. This is not new. JFK perhaps ushered in this phase of politics. His family links to Hollywood were strong and his father Joe understood the importance of image and simple and compelling ideas, whether they were right or wrong. Ronald Reagan was the master of this domain and he was a hedgehog.

What is worrisome is these same hedgehog like characteristics are also basically markers of bad judgment. How do we address this? Is it addressable? I suspect it is not and represents a basic human limitation. One approach may be to push to limit the ability of parties to appeal to voters through some sort of legislative or regulatory action. I have little confidence that this will yield results which leave us better off. In my opinion, these observations represent a compelling reason to create limits on what should or can be done via exercise of political power.

Saturday, February 6, 2016

Innumeracy and catastrophizing; partners in creating medicine's anxiety disorder

I am currently reading Richard Thaler's book "Misbehaving". Perhaps I spend too much time thinking about this subject, but I am constantly reminded t hat even the most educated professionals that I work with are blind to how they "misbehave" as Thaler describes. He uses t his term to describe behaviors and decisions made by individuals that are simply not rational.

His path into these studies came from seeing inconsistencies in how the world of economics initially viewed human decision making, before the widespread introduction of concepts of behavioral economics. He noted that from a purely economic sense, people made really crazy decisions. They did not behave like what was referred in the field as Homo economist (or Econs for short). Basically, the numbers did not add up.

These sorts of inconsistencies are certainly not limited to economic decisions. They touch all decisions made by people in all walks of life. They are simply rampant in health care and the misbehaving is certainly not limited to patients and consumers of health care. I would argue that the business model upon which much of current health care delivery is based is very dependent upon getting all actors to "misbehave". The growing consumption of services in the health care arena is driven by almost universal innumeracy displayed by providers and consumers alike, which is leveraged to create widespread catastrophizing of potential consequences. The anxiety created serves as a powerful marketing tool. Those of us within the health care delivery world derive substantial financial benefit from our patients being innumerate and from being innumerate ourselves.

One particular leverage point is we all know what everyone's final fate will be and it terrifies most if not all of us. We can point to the potential for catastrophe and ultimately we will always be right. While we cannot dismiss that fact that every single one of our patient's lives will be marked by the ultimate catastrophe, that being one's own death, we also must realize that the stakes involved with every medical decision cannot be viewed as tightly linked to this outcome. Like the undesirable outcome for any given person when all of their personal decisions are coupled in their mind invariably to potential catastrophic outcomes, if medical care operates by catastrophizing everything, we will end up with a professional anxiety disorder.

We are already there. The medical profession suffers from anxiety disorder which is brought about and aggravated by our inbred tendency to catastrophize everything. It is dysfunctional.

One particular leverage point is we all know what everyone's final fate will be and it terrifies most if not all of us. We can point to the potential for catastrophe and ultimately we will always be right. While we cannot dismiss that fact that every single one of our patient's lives will be marked by the ultimate catastrophe, that being one's own death, we also must realize that the stakes involved with every medical decision cannot be viewed as tightly linked to this outcome. Like the undesirable outcome for any given person when all of their personal decisions are coupled in their mind invariably to potential catastrophic outcomes, if medical care operates by catastrophizing everything, we will end up with a professional anxiety disorder.

We are already there. The medical profession suffers from anxiety disorder which is brought about and aggravated by our inbred tendency to catastrophize everything. It is dysfunctional.

His path into these studies came from seeing inconsistencies in how the world of economics initially viewed human decision making, before the widespread introduction of concepts of behavioral economics. He noted that from a purely economic sense, people made really crazy decisions. They did not behave like what was referred in the field as Homo economist (or Econs for short). Basically, the numbers did not add up.

These sorts of inconsistencies are certainly not limited to economic decisions. They touch all decisions made by people in all walks of life. They are simply rampant in health care and the misbehaving is certainly not limited to patients and consumers of health care. I would argue that the business model upon which much of current health care delivery is based is very dependent upon getting all actors to "misbehave". The growing consumption of services in the health care arena is driven by almost universal innumeracy displayed by providers and consumers alike, which is leveraged to create widespread catastrophizing of potential consequences. The anxiety created serves as a powerful marketing tool. Those of us within the health care delivery world derive substantial financial benefit from our patients being innumerate and from being innumerate ourselves.

The problem with free stuff

From the NYT -

Free electricity and Puerto Rico

Note that between the declaration of free and the unwinding took over seventy years....

Free electricity and Puerto Rico

Note that between the declaration of free and the unwinding took over seventy years....

Sunday, January 24, 2016

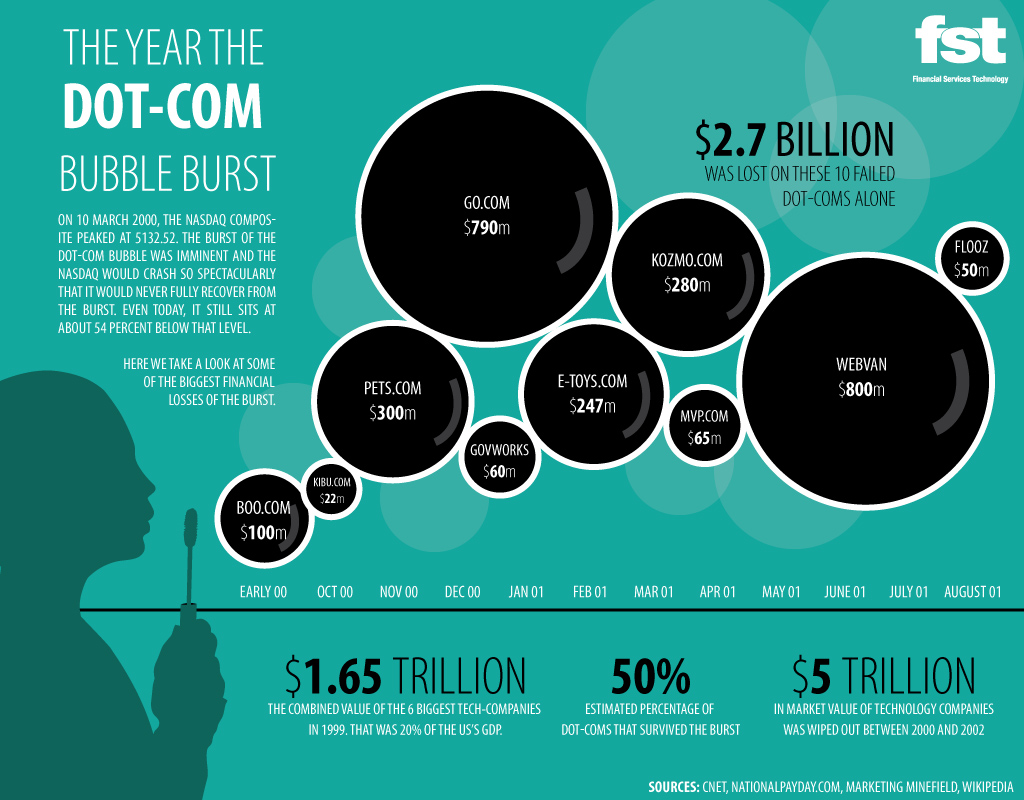

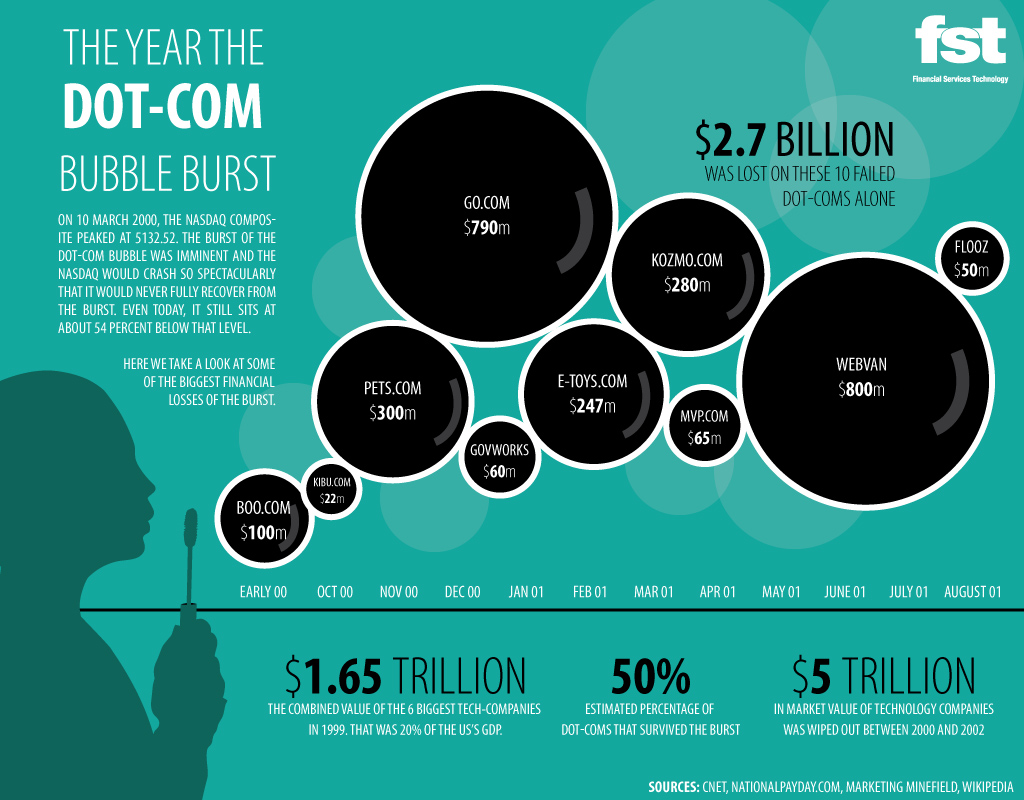

Financials bubble through the ages

Tulip Bubble

South Sea Island Bubble

Home mortgage bubble

And from the BBC news...

http://www.bbc.com/news/education-35343680

South Sea Island Bubble

Home mortgage bubble

And from the BBC news...

http://www.bbc.com/news/education-35343680

Coproduction in health care

I have been introduced to an interesting concept, that of co-production. I came upon this concept when I read an article published in BMJ Quality and Safety. (Link) It is actually such an intuitive concept that it is hard to imagine why it did not occur to me and everyone else previously. I guess that is just how ideas are.

In manufacturing, those who produce goods such as cars or consumables do not directly rely on those use consume and use those products to produce them. The end users may influence the characteristics of the products but they play little or no role in product manufacture. Consumers do not play a substantial role in the quality of the final product, whether that be automobiles or chicken pot pies.

The service industry is different. Victor Fuchs noted in 1968 that the new service economy was different from the old manufacturing economy in that the producers and consumers of services worked together to create value. Later Alfred Toffler described the next generation of consumers which he referred to as "prosumers", linking the previously separated function of production and consumption to maximize consumer value and minimize producer cost.

For example, one might hire a financial professional to help with retirement planning. No matter how good the advice of the professional, the final product depends upon the consumer. If the consumer does not follow the advice and put away money for the future, the final product will be substandard, no matter how good the advice. Similarly, if one gives your tax professional the wrong data, the final product of the tax return will not be up to snuff.

This concept is also very appropriate for many aspects health care delivery. For patients who present with a diagnostic problem, if they are not capable or willing to provide accurate or complete histories or reviews of systems, they are much less likely to receive accurate diagnoses. For patients who undergo surgery or other interventions who are then discharged home, if they are not willing or capable of following care instructions (or have not been appropriately educated), the outcomes of the interventions are much less likely to be favorable. For patients with chronic disorders where most of the care happens at home, their contributions and buy in may be most essential to optimal outcomes.

However, the co-production involves not just a given provider and a given patient, but teams of providers and other teams which may include patients, their families, and perhaps other patients.

How do we get better outcomes? You have to first figure out what you are trying to produce and then figure out who are the key players in co-producing the desired outcomes. This is going to take some major culture change, in both patients and professionals with health care delivery.

Saturday, January 23, 2016

Assault on research transparency

We all suffer from various forms of isolation, some of it self imposed. I recently read the book, "The big sort" which identifies how Americans are increasingly self sorting in terms of where they live and with whom they associate. The authors come up with a compelling story about the results of that sort, which is we are increasingly unaware of opposing world views and opinions. The New England Journal recently published an editorial which I can only explain on the basis of scientific isolation. In this editorial, the Editor of the NEJM, Jeffery Drazen expresses reservations regarding data sharing and possible unintended consequences. (NEJM). I have to admit that he raises legitimate questions:

These are difficult to address issues which should be dealt with in the open! If these issues are part of the original data set upon which conclusions are drawn, all of the readers and consumers of the information should be aware of these potential limitations. Putting such data in the hands of an extended set of interested people should do nothing but add value to the original studies.

He then goes on to state:

Obviously no one is going to make huge investments of time and effort to amass data sets only to have them coopted immediately. However, once one puts a publication in the public realm, the data upon which conclusions were drawn should be available to readers of that work.

The concern that the data could be reinterpreted with different conclusions seems frankly ridiculous. That this was published in one of the most prestigious medical journals in the world by the senior editor is outright embarrassing. Who did he have to critique this? He obviously has sorted himself away from necessary and critical peers who should have provided feedback to him and help him recognized the nonsense that this editorial is, before he published it.

However, many of us who have actually conducted clinical research, managed clinical studies and data collection and analysis, and curated data sets have concerns about the details. The first concern is that someone not involved in the generation and collection of the data may not understand the choices made in defining the parameters. Special problems arise if data are to be combined from independent studies and considered comparable. How heterogeneous were the study populations? Were the eligibility criteria the same? Can it be assumed that the differences in study populations, data collection and analysis, and treatments, both protocol-specified and unspecified, can be ignored?

These are difficult to address issues which should be dealt with in the open! If these issues are part of the original data set upon which conclusions are drawn, all of the readers and consumers of the information should be aware of these potential limitations. Putting such data in the hands of an extended set of interested people should do nothing but add value to the original studies.

He then goes on to state:

A second concern held by some is that a new class of research person will emerge — people who had nothing to do with the design and execution of the study but use another group’s data for their own ends, possibly stealing from the research productivity planned by the data gatherers, or even use the data to try to disprove what the original investigators had posited. There is concern among some front-line researchers that the system will be taken over by what some researchers have characterized as “research parasites.”What? Research work requires an investment of time and money, usually lots of each. The product of that investment may be data and from that are derived publications and hopefully some sort of impact on the world. If smart and motivated people can derive additional value from data derived from the original research teams, that is NOT parasitic. Depending upon who funded the research and who owns the data, the original parties may rightfully expect to derive some compensation and expect that they have a right to some portion of that additional value derived from the original data sets.

Obviously no one is going to make huge investments of time and effort to amass data sets only to have them coopted immediately. However, once one puts a publication in the public realm, the data upon which conclusions were drawn should be available to readers of that work.

The concern that the data could be reinterpreted with different conclusions seems frankly ridiculous. That this was published in one of the most prestigious medical journals in the world by the senior editor is outright embarrassing. Who did he have to critique this? He obviously has sorted himself away from necessary and critical peers who should have provided feedback to him and help him recognized the nonsense that this editorial is, before he published it.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)